Contents

Introduction

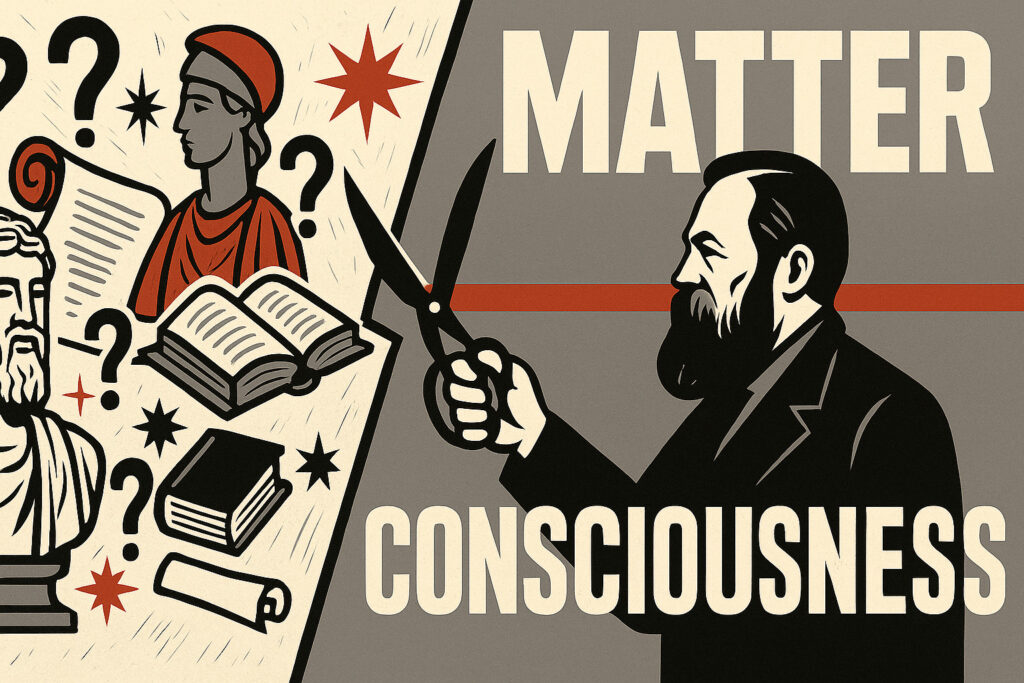

Soviet philosophy textbooks routinely asserted that “the fundamental question of philosophy is the question of the relation between matter and consciousness.” At first sight this formulation appears unobjectionable. Philosophers across many epochs indeed grappled with the problem of how thought relates to being, and how spirit relates to nature.

Yet in these textbooks the claim was presented not as one among many possible philosophical perspectives, but as self-evident, as the sole point of departure. From the multitude of questions that philosophy might pose, one was selected and elevated to the rank of “fundamental.” Moreover, the notion of “relation” was interpreted narrowly and dogmatically: the issue was reduced to the priority of either matter or consciousness.

The consequence was the reduction of philosophy to a binary alternative, and the constriction of its intellectual field to an ideological test. This formula, however, did not emerge organically. It was introduced by Friedrich Engels at the close of the nineteenth century and reflected less the pursuit of philosophical truth than the ideological imperatives of its historical moment. To see how this transformation occurred, one must return to the specific text in which Engels first articulated it.

Historical Context

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, classical German philosophy entered a period of crisis. The Hegelian system no longer provided a unifying paradigm: its sweeping dialectic of the world as “absolute spirit” ceased to orient the discipline. Hegel’s successors preserved fragments of his thought, but the project as a whole disintegrated into disparate strands.

Feuerbach sought to effect an anthropological turn, relocating philosophy onto the terrain of human nature. Yet he himself remained suspended between theology and materialism.

Concurrently, the natural sciences advanced rapidly—physics, chemistry, biology—particularly following Darwin’s theory of evolution. Against this backdrop, philosophy risked losing its authority as the “queen of the sciences” and dissolving into the specialized disciplines.

Marx and Engels aimed to demonstrate that philosophy did not vanish but assumed a new function: it became the theoretical armament of the workers’ movement. To serve this purpose, however, philosophy had to be simplified and recast.

Engels and the “Great Fundamental Question”

In Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy (written 1876, published 1886), Engels introduced what he termed “the great fundamental question of philosophy”:

“The question of the relation of thinking to being, of spirit to nature, is the great fundamental question of all philosophy.”

He then bifurcated the question: the first aspect concerns primacy—whether matter or consciousness is foundational; the second concerns the knowability of the world, to which he proposed “practice”—experiment, industry, technology—as the decisive criterion.

Three crucial moves are at work here:

- He isolated a single opposition—thought versus being, consciousness versus matter.

- He declared this opposition central and “fundamental” for the entirety of philosophy.

- He divided philosophers into two opposing camps: idealists and materialists.

Philosophy thereby ceased to be a field of plural inquiries and became a battleground of two hostile camps.

The Functions of Engels’s Formula

Engels’s conceptual reduction fulfilled several overlapping functions.

Polemical Function

It distanced Engels from the legacies of Hegel and Feuerbach while simultaneously laying claim to their authority. The rhetoric of a “great question” was preserved, but transformed into a utilitarian scheme.

Ideological Function

Marxism sought to constitute itself as a “scientific worldview.” To this end it needed to oppose itself both to religion and to “bourgeois philosophy.” A clear binary was the most effective instrument: materialism equated with science and progress, idealism with religion and reaction.

Educational Function

The workers’ movement required easily transmissible categories. Hegel’s elaborate dialectics were inaccessible to non-specialists. By contrast, the dichotomy of two camps—science/materialism versus religion/idealism—could be readily disseminated in pamphlets and agitational speeches.

In short, the formulation was less a philosophical discovery than a deliberately fashioned instrument of ideological mobilization.

Hidden Axioms of the “Fundamental Question”

Beneath its apparent clarity, Engels’s schema introduced a series of unacknowledged presuppositions.

The Axiom of Derivation

The question “what is primary—matter or consciousness?” presupposes that one must be derived from the other. Consciousness must either “emerge” from matter, or matter must be “produced” by consciousness. Alternatives—such as their co-originality, mutual dependence, or common derivation from a deeper principle—are excluded in advance.

The Temporal Substitution

The language of “primacy” carries a temporal connotation, suggesting chronological sequence: that which came earlier versus that which came later. Even when intended as ontological priority, the phrasing surreptitiously smuggles in a temporal framework. Thus the question implicitly presumes the absoluteness of time—a presupposition that twentieth-century philosophy and physics have placed in serious doubt.

The Reduction of Philosophical Diversity

The history of philosophy is collapsed into a taxonomy of two camps. Plato is rebranded an “objective idealist,” Aristotle a “materialist,” Hegel an “idealist,” Spinoza a “materialist,” and so on. The richness of their own intellectual projects is erased; what remains is a crude classification into “ours” and “theirs.”

As the Short Course of the History of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) (1938) codified:

“The highest question of all philosophy, says Engels, is the question of the relation of thinking to being, of spirit to nature… Philosophers divided into two great camps according to how they answered this question… Those who regarded nature as primary joined the various schools of materialism.”

From Formula to Dogma

Within Soviet philosophy Engels’s formulation was absolutized. It entered every curriculum and structured every introduction to philosophy.

- Students were required to accept that there was a single “fundamental question,” defined precisely in these terms.

- Philosophers of the past were arranged into camps: “materialist—ours,” “idealist—theirs.”

- Philosophy itself was reconstructed as a three-step procedure: answer the fundamental question (the correct answer being “matter is primary”), then build a worldview accordingly.

The initiation into philosophy thus became less an inquiry than a political oath of allegiance.

The Short Course proclaimed:

“Matter, nature, being represent objective reality, existing independently of consciousness; matter is primary… and consciousness is secondary, derivative, as the reflection of matter.”

And further:

“The most decisive refutation of these… philosophical distortions lies in practice, namely in experiment and industry… thereby the ‘thing-in-itself’ was transformed into a thing for us.”

In this manner philosophy was transformed from open inquiry into ideological catechism.

The Logical Misstep

The gravest flaw in Engels’s schema lies in its substitution of a genuine metaphysical question—the question of archē, of first principle or condition of possibility—with a dispute between two already derivative phenomena.

Matter and consciousness, as experienced, are themselves constituted realities. To make them ultimate principles is to mistake effects for causes, conditions for consequences. The question is analogous to asking whether law or the state is “primary”: both presuppose a deeper ground of possibility.

By elevating a partial opposition to the status of universal framework, Engels effectively collapsed philosophy into a reductive binary.

What Philosophy Retains

From this analysis a crucial lesson follows: philosophy need not, and perhaps must not, be organized around a single “fundamental question” conceived as a binary.

- Philosophy may investigate first principles, but in the form of conditions of possibility, not chronological precedence.

- It may expose the hidden axioms embedded in language, revealing how conceptual frameworks naturalize dogmas.

- It may preserve the plurality of inquiry against its reduction to the logic of camps and oppositions.

Only in this way does philosophy reclaim its vocation as the art of distinction, the practice of critical freedom, and the pursuit of meaning.

Conclusion

Engels’s construction of “the fundamental question of philosophy” arose in a determinate historical conjuncture and served ideological ends. It introduced hidden axioms—of derivation, of temporality, of binary camps—that narrowed the horizon of inquiry.

The result was a substitution: philosophy was reduced to the dispute over whether matter or consciousness comes “first,” rather than exploring the deeper grounds that make both possible.

To recognize this substitution is to reopen the horizon of philosophy: not as a test with predetermined answers, but as an open practice of questioning; not as a binary reduction, but as a search for meaning across unbounded horizons.

Bibliography

- Engels, Friedrich. Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy. Written 1876, first published 1886.

- All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks). Short Course of the History of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks). Moscow: Gospolitizdat, 1938.

- Lenin, Vladimir I. Philosophical Notebooks; Materialism and Empirio-Criticism. 1909.

- Marx, Karl. Capital, Vol. I. Afterword to the second German edition, 1873.