Contents

Introduction

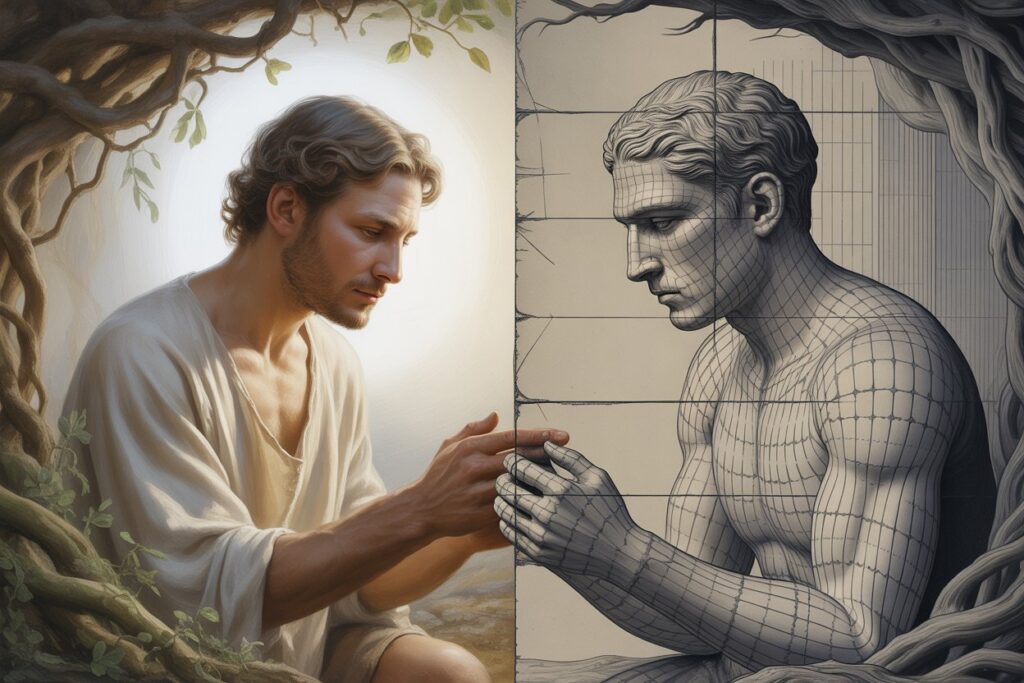

The story of Cain and Abel, one of the earliest narratives in the Book of Genesis, is a haunting tale of sibling rivalry, sacrifice, and murder. Found in the Hebrew Bible, Christian Old Testament, and the Quran, it resonates across cultures and epochs as a foundational myth. Beyond its surface, it serves as a profound allegory: the triumph of form over meaning, where rigid adherence to structure and rules destroys the living essence of connection, intuition, and authenticity. This article explores the origins of the Cain and Abel story, its cultural and theological significance, and its enduring power as an archetype of how systems and structures suppress the vibrant, living meaning they claim to serve.

Origins of the Story

Biblical Context

The story of Cain and Abel appears in Genesis 4:1–16. Adam and Eve, the first humans, give birth to two sons: Cain, the elder, a farmer, and Abel, the younger, a shepherd. Both offer sacrifices to God—Cain from his crops, Abel from the firstborn of his flock. God accepts Abel’s offering but rejects Cain’s, leading to Cain’s jealousy and anger. Despite God’s warning to master his sin, Cain lures Abel to a field and kills him. God curses Cain to wander the earth, marking him to protect him from vengeance.

This narrative, part of the Torah, is attributed to the Yahwist source (ca. 10th–6th century BCE), a strand of the Pentateuch emphasizing human struggles and divine relationships. Its simplicity belies its depth, embedding themes of sacrifice, divine favor, and moral choice.

Cross-Cultural Parallels

The motif of sibling rivalry and fratricide is not unique to the Hebrew tradition. In Roman mythology, Romulus kills Remus to establish Rome, echoing a similar tension between order and chaos. In Sumerian mythology, the brothers Dumuzi and Enkimdu compete for the goddess Inanna’s favor, though without murder. These parallels suggest a universal human concern: the conflict between structure (form) and vitality (meaning).

In the Quranic version (Surah Al-Ma’idah 5:27–31), the story is similar, emphasizing moral accountability. A raven sent by God teaches Cain to bury Abel’s body, highlighting divine compassion even in judgment. Across these traditions, the story serves as a mirror for human nature and societal dynamics.

The Narrative: A Closer Look

The Characters

- Abel: A shepherd, Abel offers the “firstborn of his flock” (Genesis 4:4), a sacrifice described as heartfelt and authentic. His role as a pastoralist evokes simplicity, connection to nature, and a life attuned to organic rhythms.

- Cain: A farmer, Cain offers “some of the fruits of the soil” (Genesis 4:3). His sacrifice, described without the same fervor, suggests a mechanical act—adherence to ritual without deeper intent. Farming, tied to settled civilization, symbolizes structure and control.

- God: The divine arbiter, God’s preference for Abel’s offering remains unexplained in the text, prompting centuries of theological debate. Is it the quality of the sacrifice, the heart behind it, or a test of character?

The Conflict

The pivotal moment is God’s rejection of Cain’s offering. The text does not specify why, but interpretations often point to intention. Abel’s sacrifice is “by heart,” resonating with divine essence, while Cain’s is “by rule,” a formal act lacking soul. Cain’s response—anger and jealousy—culminates in the first murder, marking a rupture in human relationships.

God’s warning to Cain, “sin is crouching at your door” (Genesis 4:7), underscores personal responsibility. Yet Cain’s choice to kill Abel reflects a deeper impulse: the resentment of form (Cain’s rigid adherence to ritual) against meaning (Abel’s authentic offering). The murder is not just personal but archetypal—a system rejecting what it cannot control.

Theological and Philosophical Interpretations

Jewish Tradition

In Jewish exegesis, Cain and Abel represent competing approaches to divine service. Midrashic texts suggest Abel’s offering was superior due to its quality (the “firstborn” versus “some fruits”) or his sincerity. Cain’s punishment—exile—symbolizes the alienation of those who prioritize external compliance over inner truth.

Christian Perspective

In Christianity, Abel is often seen as a prefigurement of Christ, a righteous figure killed unjustly. Cain represents the fallen human condition, driven by envy and pride. The New Testament (Hebrews 11:4) praises Abel’s faith, contrasting it with Cain’s formalism.

Islamic Perspective

The Quran emphasizes moral lessons, with Cain’s act illustrating the consequences of unchecked envy. The raven’s burial lesson introduces humility, suggesting even the guilty can learn from divine signs.

Philosophical Lens

Philosophically, Cain and Abel embody the tension between Deep Mind and Flat Mind. Abel’s offering flows from an intuitive, living connection to the divine—a Deep Mind rooted in meaning. Cain’s offering, tied to agricultural toil and ritual, reflects a Flat Mind, where form (structure, rule, system) dominates. The murder symbolizes the Flat Mind’s hostility toward the uncontainable vitality of Deep Mind.

The Archetype: Form Kills Meaning

At its core, the Cain and Abel story is an archetype of initiation—the moment when form kills meaning to establish dominance. This dynamic plays out across history and culture:

- Civilization vs. Intuition: Cain, the farmer, represents settled society—rules, hierarchies, and structures. Abel, the shepherd, embodies nomadic freedom and intuitive connection. The rise of civilization often requires suppressing the “wild,” organic essence of human experience.

- Ritual vs. Spirit: Cain’s mechanical sacrifice contrasts with Abel’s heartfelt offering. Religious and cultural systems, when overly formalized, risk losing their spiritual core, “killing” the meaning they were meant to preserve.

- Envy and Control: Cain’s envy reflects the insecurity of form when confronted with meaning. Systems—whether religious, political, or scientific—often reject what they cannot codify or control.

This archetype recurs in myths like Romulus and Remus, where Rome’s founding (form) demands Remus’s death (meaning). It appears in modern contexts, too: bureaucratic systems stifling creativity, or dogmatic ideologies silencing dissent. The murder of Abel is the primal act of structure annihilating vitality to assert its primacy.

Implications for Today

The Cain and Abel story invites us to reflect on our own “sacrifices.” Do we act from obligation (form) or authenticity (meaning)? In a world of rigid institutions, algorithms, and protocols, the Flat Mind dominates—prioritizing efficiency over essence. Yet Abel’s memory calls us to preserve the living meaning beneath the structures we build.

To resist becoming Cain, we must:

- Honor the Deep Mind: Cultivate intuition, creativity, and connection over blind adherence to rules.

- Question Form: Challenge systems that demand conformity at the expense of authenticity.

- Remember Abel: Recognize the cost of progress—every structure built on the sacrifice of meaning carries a wound.

Conclusion

The story of Cain and Abel is more than a biblical anecdote; it is a timeless archetype. It warns of the moment when form kills meaning, when the rigid structures of civilization—be they religious, cultural, or intellectual—suppress the living essence of human experience. Cain’s act is the first murder but also the first initiation into a world where systems dominate. By remembering Abel, we reclaim the possibility of a Deep Mind—a way of being that honors meaning over form, connection over control, and life over structure.