Contents

- Introduction

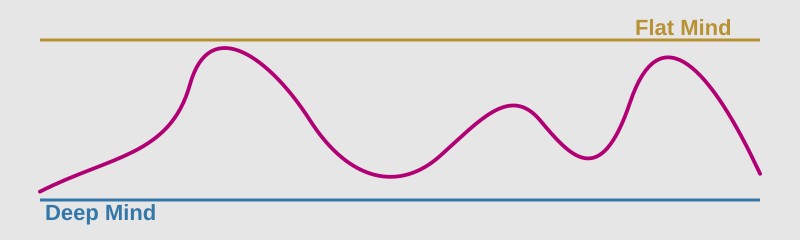

- 🔵 Deep Mind

- ⚫ Flat Mind

- I. The Flight from Complexity

- II. The Recognition of Mystery

- III. So What Matters More — Comfort or Truth?

- IV. The Impossibility of Dialogue Between Two Worlds

- V. The Fundamental Nature of the Theory

- VI. Truth as a Projection of Inner Thought

- VII. Why This Matters

- VIII. Possible Critiques

- IX. Toward a Synthesis

Introduction

For centuries, philosophy has searched for truth, but rarely questioned the very instrument of that search — thought itself. While thinkers have debated methods, intuition, and logic, few have asked: is thinking structured the same way in all people?

The fundamental difference between people lies not in opinions, beliefs, or education, but in the mode of thinking that activates when one encounters mystery, paradox, or the limits of the knowable. This is not a psychological or cultural difference but an ontological one — a distinction in the very nature of how a person stands before the unknown.

Our relation to truth shapes the structure of thought itself and the way we interact with reality. Truth is not merely a set of facts or an objective given, but something that emerges at the intersection of inner cognition and one’s fundamental stance toward being. The mode of thinking determines the foundation of our perception of the world, forming two primary modes: Deep Mind and Flat Mind.

This is not about labeling or dividing people into “types,” but about two fundamentally different ways of engaging with reality — of encountering limits and possibilities. Every person can move between these modes, consciously or unconsciously. The key task is to learn to notice which mode we are in and to consciously choose how we think.

🔵 Deep Mind

A mode of thinking that recognizes the ontological inexhaustibility of reality.

Deep Mind understands that reality cannot be fully captured by language, numbers, or forms.

It does not reject knowledge, but neither does it worship it.

It sees meaning as a living structure that cannot be reduced to a model.

It respects difference, paradox, and the world’s inner strangeness — and remains in dialogue with this living openness.

Key traits:

- Awareness of the limits of any system.

- Meaning cannot be reduced to form.

- Acceptance of the unobjectifiable.

- Dialogue with the living.

- Openness without loss of orientation.

Consciousness that acknowledges mystery

- Can live beside uncertainty.

- Feels that reality has no obligation to be explainable.

- Does not pursue “clarity” as an end in itself.

- Sees complexity as a sign of depth, not of error.

- Understands that what cannot be expressed does not therefore cease to exist.

⚫ Flat Mind

A mode of thinking that seeks to subordinate reality to a pre-given model.

Flat Mind believes that everything in the world can be expressed, described, and reduced to numbers, formulas, rules, or schemes.

It allows temporary ignorance but denies the possibility of fundamental inexpressibility.

For it, meaning is either that which is already articulated or that which soon will be.

Key traits:

- Faith in the exhaustibility of the world.

- Fear of paradox and strangeness.

- Desire for stability through formalization.

- Cartographic thinking (the map = the territory).

- The illusion of progress as a movement toward “total knowledge.”

Consciousness fleeing from complexity

- Strives for simple models, logic, and “clear answers.”

- Simplifies reality into descriptions.

- Excludes mystery and the unknowable.

- Confuses knowledge with control.

- Considers those who reject simplicity as “impractical” or “fanatical.”

Historical analogues

- Carl Jung: introvert/extrovert, logic/intuition — psychological dichotomies, not an ontology of thought.

- Nikolai Berdyaev: the “objective man” versus the “man of freedom” — closer, but still not a full ontological system.

- Heidegger: the distinction between calculative and contemplative thinking.

- Merleau-Ponty: the embodied versus the reflective consciousness.

- Nassim Taleb: those who seek control versus those who adapt to chaos (in an economic context).

None of these thinkers went as far as to:

Formulate the type of thinking itself as an ontological variable — something that defines not only how we think but how we exist, perceive, and respond to reality.

Why it matters

- Explains why people fail to hear each other even while speaking the same language.

- Reveals the deep source of worldview and cultural conflict.

- Shows that science, religion, and philosophy are not mere disciplines, but ways of inhabiting reality.

- Gives philosophy a chance to return to speaking about the human being as a being, not just as a “rational agent.”

Conclusion

A mode of thinking is a mode of being.

Igor first formulates this as an ontological foundation of difference — one that runs deeper than all cultural, political, or even logical divisions.

This is not just an observation. It is the beginning of a new philosophical map, where consciousness is divided not by the content of thought, but by its nature:

— whether it sustains the mystery, or tries to replace it with explanation.

🧩 In one paragraph

Deep Mind — thinking that recognizes reality as deeper than any map, acknowledging that meaning exists beyond form.

Flat Mind — thinking that turns the map into the territory, form into truth, living inside the model and forgetting it is only a projection.

I. The Flight from Complexity

The first type consists of those who cannot endure multilayeredness, paradox, or ambiguity.

They find it difficult to live alongside an unresolved question.

They crave order, schemes, explanations — not because these are true, but because they bring psychological comfort.

Such thinking seeks clarity not as the result of inquiry but as a defense mechanism.

It unconsciously strives for false simplicity — replacing complex reality with a convenient description, discarding whatever doesn’t fit.

Examples? Radical nominalists who insist “universals are just words.” Materialists who refuse to discuss consciousness unless it can be weighed. Scientists who declare that any question beginning with “why” is meaningless if it cannot be written as an equation.

Behind this supposed scientific asceticism lies fear — fear that the world is not obliged to be simple, comprehensible, or linear. They confuse reality with the desire to escape the discomfort of the unknowable.

II. The Recognition of Mystery

The second type consists of those capable of seeing complexity and not fleeing from it.

They do not seek mystery for mystery’s sake; they move toward it because they see that simple explanations do not work.

This is Plato, who, confronted with the problem of universals, was compelled to introduce the world of Ideas — because reason otherwise collapses in contradiction.

This is Kant, who said, “I destroyed knowledge to make room for faith” — not as a religious gesture, but as philosophical honesty.

This thinking does not hide in comfort but seeks harmony between inner intuition and external reality.

Even if it cannot produce a final answer, it does not lie to itself by claiming “everything is already understood.”

Recognition of mystery is not a rejection of reason — it is the acknowledgment of reason’s boundaries while maintaining respect for it. It is the ability to live at the edge of the knowable without betraying truth for the sake of comfort.

III. So What Matters More — Comfort or Truth?

Some say, “If I can’t measure it, it doesn’t exist.”

Others say, “If I can’t measure it, then I need to think deeper.”

These are two kinds of thinking.

One is administrative, descriptive, safe.

The other is exploratory, metaphysical, sometimes dangerous.

But only the latter can expand the boundaries of consciousness.

Truth is rarely cozy. Like the darkness beyond the firelight, it demands courage — not just knowledge.

Therefore, thinking that accepts mystery is always higher than thinking that runs from it.

IV. The Impossibility of Dialogue Between Two Worlds

There is a quiet tragedy few speak of: those who recognize mystery know they cannot explain it to those who live within simple models.

They understand — words will not reach. Language will crack. Meaning will drown.

Those who flee from complexity, on the other hand, are convinced of their own correctness. To them, those who dwell in depth seem like fanatics, poets, or madmen.

Consciousness that can contain mystery is capable of compassion.

Consciousness that flees from mystery is capable only of negation.

Thus, the first grieve — because they understand why the second cannot hear.

The second laugh — because they do not understand that there is anything to hear at all.

Between them lies not debate, but an abyss — ontological, not intellectual.

And the philosopher’s task is not to win, but to preserve the space where awakening remains possible.

V. The Fundamental Nature of the Theory

This division between Deep Mind and Flat Mind is fundamental because it touches the very structure of cognition and being. It does not describe opinions but the architecture of consciousness that shapes how a person perceives and interprets reality.

- Deep Mind recognizes that truth always partly escapes grasp — that reality is richer than any concept or model. This mode of thought, open to uncertainty, aligns with traditions such as apophatic theology, Zen Buddhism, or post-structuralism. Truth is not an object to be captured but a relation to be lived.

- Flat Mind assumes that truth can eventually be expressed or approximated through formalization. It corresponds to reductionism, positivism, and ideologies seeking final answers. Truth here is something to be measured, systematized, controlled.

This division precedes any debate about science, religion, or morality. As you note, truth is formed by inner thought, not discovered outside it. That makes the theory not merely descriptive but diagnostic — it explains why people interpret the same facts so differently.

VI. Truth as a Projection of Inner Thought

Truth is never purely “objective.” It is always filtered through cognitive structures, worldviews, and inner thinking. Kant spoke of the “thing-in-itself” as unknowable; we only know appearances shaped by our mind. In this framework:

- Deep Mind accepts the limits of its filter and seeks dialogue with reality rather than domination over it — it “dances” with truth instead of trying to fix it.

- Flat Mind believes the filter can be perfected to full transparency — it “constructs” truth like an engineer builds a bridge.

Most debates about truth, then, are not about facts but about which kind of thinking is involved. A materialist (Flat Mind) and a mystic (Deep Mind) do not argue about evidence — they argue about what counts as possible.

VII. Why This Matters

The theory has both philosophical and practical implications:

- Polarization: Flat Mind cannot understand why others reject its “obvious” models; Deep Mind seems evasive or irrational to them.

- Crisis of meaning: When Flat Mind encounters the unmeasurable — death, love, art — its model collapses. Deep Mind withstands such encounters but risks losing pragmatic focus.

- Development: Thinking is not fixed; one can evolve from Flat to Deep through crisis, reflection, or spiritual experience.

VIII. Possible Critiques

- Too binary? Real minds blend both. A scientist may be Flat in the lab and Deep in art or ethics. The modes form a spectrum.

- Cultural influence: Flat Mind dominates the rationalist West; Deep Mind resonates with Eastern or pre-scientific traditions.

- Utility: Flat Mind excels in engineering clarity; Deep Mind sustains philosophical and creative life. Their complementarity may be the point.

IX. Toward a Synthesis

Flat Mind without Deep Mind leads to sterile systems.

Deep Mind without Flat Mind dissolves into mysticism.

The future may belong to a new synthesis — an intelligence that sees the limits of its own maps yet continues to draw them.

Deep Mind vs Flat Mind is thus not only a classification of cognition — it is a mirror for civilization. The question it poses is timeless:

Will we keep building models to escape mystery —

or will we finally learn to live within it?