Contents

- Introduction

- Ancient Civilizations: Mythological Origins (circa 6000 BCE – sixth century BCE)

- Mesopotamia (Sumerians and Babylonians, territory of modern Iraq, circa 6000–3000 BCE)

- Ancient Egypt (Nile Valley, circa 3000–1000 BCE)

- Ancient India (Vedic period, Indian subcontinent, circa 1500–500 BCE)

- Ancient Israel and the Near East (circa 1000 BCE – first century CE)

- Ancient China (East Asia, before the seventeenth century BCE – first century CE)

- Northern Europe (Scandinavians and Germanic tribes, circa 800–500 BCE)

- Early Greek Philosophy: Flat Models (eighth–sixth centuries BCE)

- Conclusion

Introduction

The idea of the Earth as a flat disk or slab is one of the oldest in the history of humankind. It arose from an intuitive perception of the world: the horizon appears straight, and the ground beneath one’s feet feels level. This idea dominated the mythological cosmologies of many civilizations until approximately the sixth century BCE, when alternative models began to appear in Greek philosophy. In this article, we will focus exclusively on the period when the flat Earth was the prevailing concept in people’s minds: from archaic cultures to the early Greek thinkers. We will rely on historical sources, archaeological evidence, and the writings of philosophers in order to carefully examine the chronology of these ideas.

Ancient Civilizations: Mythological Origins (circa 6000 BCE – sixth century BCE)

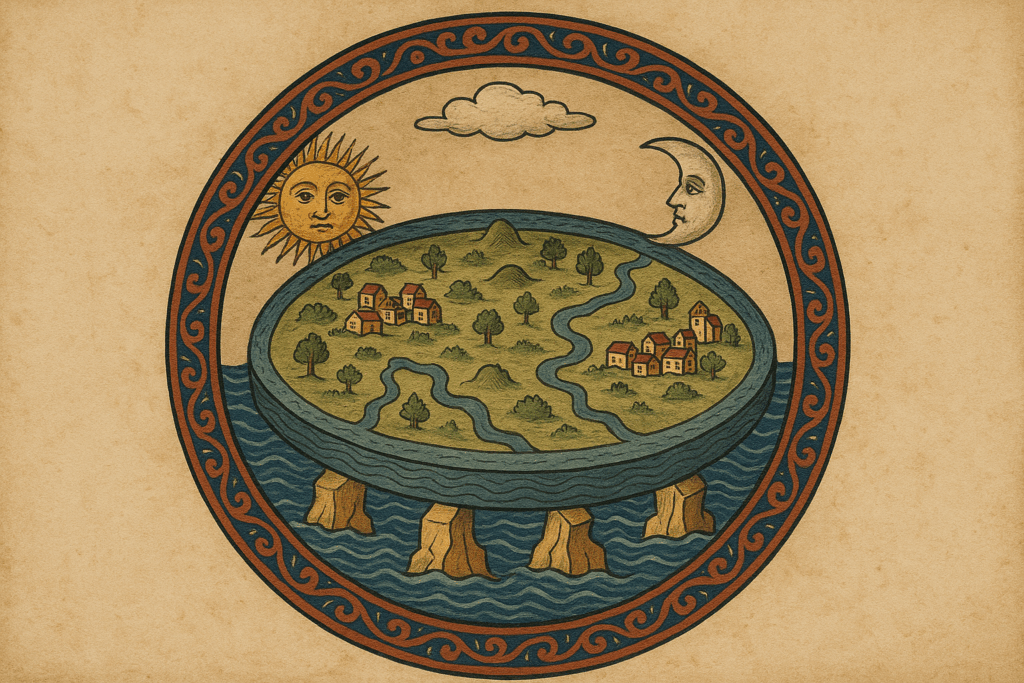

In archaic cultures, the Earth was most often depicted as a flat surface, surrounded by water or chaos, with the heavenly vault above it. This reflected everyday experience and the need for a stable “foundation” for the world. Such conceptions were nearly universal and based on myths that explained the structure of the cosmos. Below are key examples by civilization and region:

Mesopotamia (Sumerians and Babylonians, territory of modern Iraq, circa 6000–3000 BCE)

The earliest recorded conceptions of the world are found here. In Sumerian mythology, the Earth (Ki) was a flat disk floating upon subterranean fresh water (Apsu). Above it was the solid vault of heaven (An), studded with stars, and below it lay the underworld (Kur). The cosmos was divided into three levels: heaven, earth, and the netherworld. This worldview is visible in clay tablets such as the Enuma Elish (the Babylonian creation epic, circa 1800–1100 BCE), where the god Marduk creates the flat Earth from the body of the defeated goddess Tiamat.

The Babylonian “Map of the World” (Imago Mundi, sixth century BCE, found in Sippar) portrays the Earth as a circular disk with Babylon at the center, surrounded by the “bitter ocean” (Marratu) and seven islands beyond it. The Earth was supported by water, while the sky was imagined as a hemispherical dome with gates for the Sun and the Moon. These concepts shaped daily life: temples (ziggurats) symbolized mountains connecting the flat Earth with the heavens.

Ancient Egypt (Nile Valley, circa 3000–1000 BCE)

The Earth was imagined as a flat surface or valley (the god Geb), bordered by mountains or the primordial ocean (Nun — the chaos). Above the Earth arched the sky goddess Nut, forming a vault supported by the air god Shu. The Sun (Ra) sailed daily across the sky in a boat and at night passed beneath the Earth through the underworld (Duat), where it battled chaos (Apophis). This worldview is reflected in the Pyramid Texts (circa 2400–2300 BCE, in the pyramids of Saqqara) and the Book of the Dead (papyrus texts, circa 1550–50 BCE), where the Earth is depicted as a flat slab with the Nile at its center, and the world’s edges as mountains or walls. Egyptians believed the Earth floated on water, and the Nile’s floods came from rising subterranean waters. Temple art, such as that at Karnak, shows the flat Earth beneath the heavenly vault.

Ancient India (Vedic period, Indian subcontinent, circa 1500–500 BCE)

In the Rigveda (circa 1500–1200 BCE) and the Puranas, the Earth (Bhumi or Prithvi) was a flat slab or disk divided into seven continents (dvipa), surrounded by oceans. It was supported by elephants standing on a turtle (Akupara), which swam in the cosmic ocean, or by the serpent Shesha. At the center stood Mount Meru, the axis of the world. In the Mahabharata and the Ramayana (circa 400 BCE – 300 CE, with earlier roots), the Earth was depicted as a flat circle with rings of oceans — of salt, milk, and so on. Jain and Buddhist cosmologies (circa 500 BCE) also described the Earth as a flat disk with Mount Meru at the center, encircled by rings of continents and oceans. These ideas influenced architecture: stupas and temples symbolized the flat Earth beneath celestial levels.

Ancient Israel and the Near East (circa 1000 BCE – first century CE)

In the Hebrew Bible (Genesis, circa 1000–500 BCE), the Earth was a flat disk floating upon “the deep” (Tehom), with a solid heavenly dome (raqia or firmament) in which the heavenly lights were set. The “ends of the Earth” and “pillars of the Earth” were mentioned literally (in Job and the Psalms). The heavens were described as a tent or dome over the flat Earth. These ideas were inherited from Mesopotamian myths and influenced Jewish and early Christian cosmology.

Ancient China (East Asia, before the seventeenth century BCE – first century CE)

In the Gai Tian theory (circa 1000 BCE), the Earth was a flat square beneath a round dome of heaven, like a lid above a cart. The sky rotated around the Pole Star, while the Earth was supported by four pillars or floated on water. This is described in the Zhou Bi Suan Jing (circa 100 BCE). Scholars such as Zhang Heng (78–139 CE) further developed these ideas, but the Earth remained flat. Myths of the goddess Nüwa, who repaired the heavens, also implied a flat structure.

In Norse mythology (The Poetic Edda, written down in the thirteenth century CE but rooted in earlier oral traditions), the Earth (Midgard) was a flat disk created from the body of the giant Ymir. It was encircled by the ocean, within which lay the world serpent Jörmungandr. At the center stood Yggdrasil, the cosmic tree connecting nine worlds. The sky was made from Ymir’s skull, supported by dwarves. Similar flat-Earth models are found in Germanic myths.

Early Greek Philosophy: Flat Models (eighth–sixth centuries BCE)

In Ancient Greece, the idea of a flat Earth was initially dominant in myths and among early thinkers, but this was a transitional period from mythology to rational philosophy. The flat model prevailed until the mid-sixth century BCE.

Eighth–seventh centuries BCE (Homer and Hesiod, Ionia and mainland Greece)

In the Iliad and the Odyssey (circa 800 BCE), the Earth was depicted as a flat disk surrounded by the river Oceanus, from which the Sun and stars rose. Beneath the Earth lay Tartarus, the underworld. In Hesiod’s Theogony (circa 700 BCE), the Earth (Gaia) was imagined as a flat slab with roots in chaos. The shield of Achilles in the Iliad served as a microcosm: a flat disk with cities, fields, and the encircling ocean.

Sixth century BCE (Presocratics, Milesian school, Ionia)

Thales of Miletus (circa 624–546 BCE) considered the Earth a flat disk floating upon water, like a log on a river. Earthquakes, he argued, were caused by waves. Anaximander (circa 610–546 BCE) described the Earth as a flat cylinder or drum suspended in the infinite (apeiron), without support. Anaximenes (circa 585–528 BCE) imagined it as a flat disk supported by air. Anaxagoras (circa 500–428 BCE) and Democritus (circa 460–370 BCE) maintained the flat-Earth model, conceiving of it as a shallow dish or disk with a central depression for the seas.

Conclusion

This period (from the Neolithic to the sixth century BCE) is characterized by the flat Earth as an intuitive and mythological model, reflecting local experience and the need for a stable “foundation.” It was nearly universal among civilizations but displayed regional variations: a disk upon water (Mesopotamia), a slab on animals (India), a square beneath a dome (China). By the end of the sixth century BCE, doubts began to emerge in Greece, leading to new conceptions, but the flat-Earth model remained dominant in the popular imagination.